Remarkable for its staying power, the FBI’s “Ten Most Wanted Fugitives” list remains relevant and effective because it morphed into whatever media can reach the next tipster.

The multi-media goal is to empower the public to “make the world smaller” for those on the run.

The FBI’s iconic list started as a post-World War II publicity gambit, to publish headshots in an afternoon newspaper. That paper is long gone, along with the faded p.m. newsprint genre. But the idea of pushing fugitives’ pictures to the public has survived and thrived.

“The FBI has evolved from using magazines and newspaper, to television, to the Internet, and now to the use of social media and digital billboards,” said Michael P. Kortan, the FBI longtime public affairs executive who retired in February.

iTunes now offers a podcast called Wanted by the FBI. The FBI created an app by the same name, and another app specific to bank-robbery cases. Followers of FBI social media (Facebook and Twitter) can get instant information about the latest cases.

The Genesis

On February 7, 1949, The Washington Daily News published a list of 10 fugitives wanted by the FBI. The resulting fascination was so heady — our brains love lists – that media-savvy J. Edgar Hoover launched the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list the next year (March 14, 1950).

Number One on the list was Thomas James Holden, whose rap sheet included mail-train robbery, escape from Leavenworth, and unlawful flight to avoid prosecution for murder. Holden was arrested in Oregon in 1951 after a tipster identified him from a picture in the Oregonian newspaper.

Hoover’s Top Ten fugitives list was a derivative of the wanted poster. Frontier sheriffs and governors advertised rewards and eventually added photos, which qualified as “new media” in that era.

Effective by any measure

Since the FBI formalized its most-wanted list, 517 fugitives have been Top Tenners. More than nine out of 10 have been apprehended or located (484). Of that number, a third were captured/located as a result of what the FBI calls “citizen cooperation.”

The FBI located four Top Ten fugitives in 2017, six in 2016. When a Top Ten slot opens up, the FBI adds a new fugitive wanted for major crime and considered a dangerous menace to society.

The iconic list is a mirror to America’s psyche, said a New York Times think piece published in 1997. In the 1950s, the list was dominated by bank robbers, burglars, and car thieves. In the 1960s, the FBI added radicals charged with kidnapping, sabotage, and destruction of government property. The first woman was put on the list in 1968.

Mobsters and terrorists populated the list in the 1970s, followed by sexual predators, drug traffickers, and international terrorists. The FBI says these changes reflect agency priorities. Bin Laden was put on the FBI’s Top Ten list after the 1998 bombings of US embassies in Tanzania and Kenya that killed more than 200.

Media Migration

As crime changed, so did the FBI’s media positioning.

In 1987, John Walsh launched the long-running TV show “America’s Most Wanted,” which worked closely with the FBI and other law enforcement. The first fugitive profiled on the show – and the first caught – was Top Tenner David James Roberts, who was serving six consecutive life sentences in Indiana when he escaped in 1986.

In the mid-1990s, the FBI launched its website. In the spring of 1996, a 14-year-old American living in Guatemala surfed the site and recognized Top Ten fugitive Leslie Ibsen Rogge, a prolific bank robber who surrendered at the US embassy. Today, visitors to the FBI’s Most Wanted website are encouraged to download an FBI app to help identify bank robbers.

In 2007, the FBI first used digital billboards to help find fugitives, starting in Philadelphia.

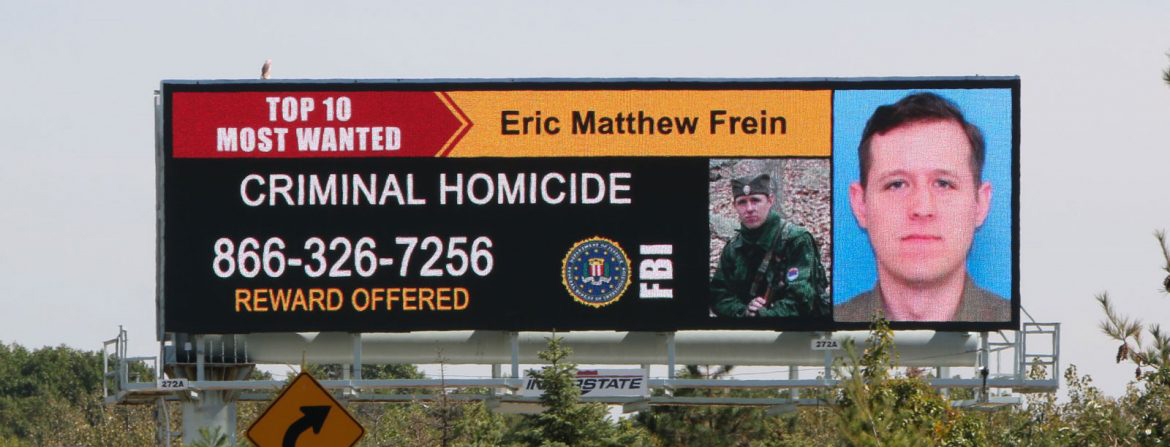

The multi-media reach of modern manhunts often prompts a domino effect of publicity. After Eric Frein allegedly shot two troopers in Pennsylvania in 2014, the FBI prepared a standard flyer.

The Frein manhunt generated overlapping publicity via print, broadcast, and social media. When the FBI activated digital billboards in six states, it prompted a new round of publicity (Frein was found hiding in a remote location).

Eric Frein most wanted billboard in Lancaster County, Pa., tonight. #EricFrein pic.twitter.com/5X9W42DCLw

— Dan Gleiter (@DanGleiter) September 21, 2014

“We now have made the world where he could hide a very, very small place,” said Edward Hanko, the FBI special agent in charge of its Philadelphia office during the Frein manhunt.

Published: March 19, 2018