Do billboards “speak?”

Yes, said a judge in Cincinnati who invalidated the city’s new targeted tax on billboards.

After six days of testimony, Common Pleas Court Judge Curt C. Hartman issued an injunction October 17 that blocked Cincinnati’s billboard tax. Billboards communicate speech, and, therefore, should not be singled out for unique taxation, the judge said.

On June 27, Cincinnati’s City Council voted 6-3 to impose a 7 percent tax on billboards or a calculation based on square footage, whichever is greater. Norton Outdoor Advertising and Lamar Advertising Company sued the city on constitutional grounds.

Lawyers who represented Norton and Lamar will explain the case in detail at the OAAA Legal Seminar on November 14 in New York City. See related Special Report here.

This article breaks down key arguments in the case:

Do billboards speak?

The city said they do not.

“The rental of billboards to show messages on behalf of paying clients may thus be distinguished as a commercial transaction that does not involve fundamental rights,” the city said in its 43-page court brief.

The judge disagreed, quoting the US Supreme Court in the Metromedia billboard case: “Billboards are a well-established medium of communication, used to convey a broad range of different kinds of messages.”

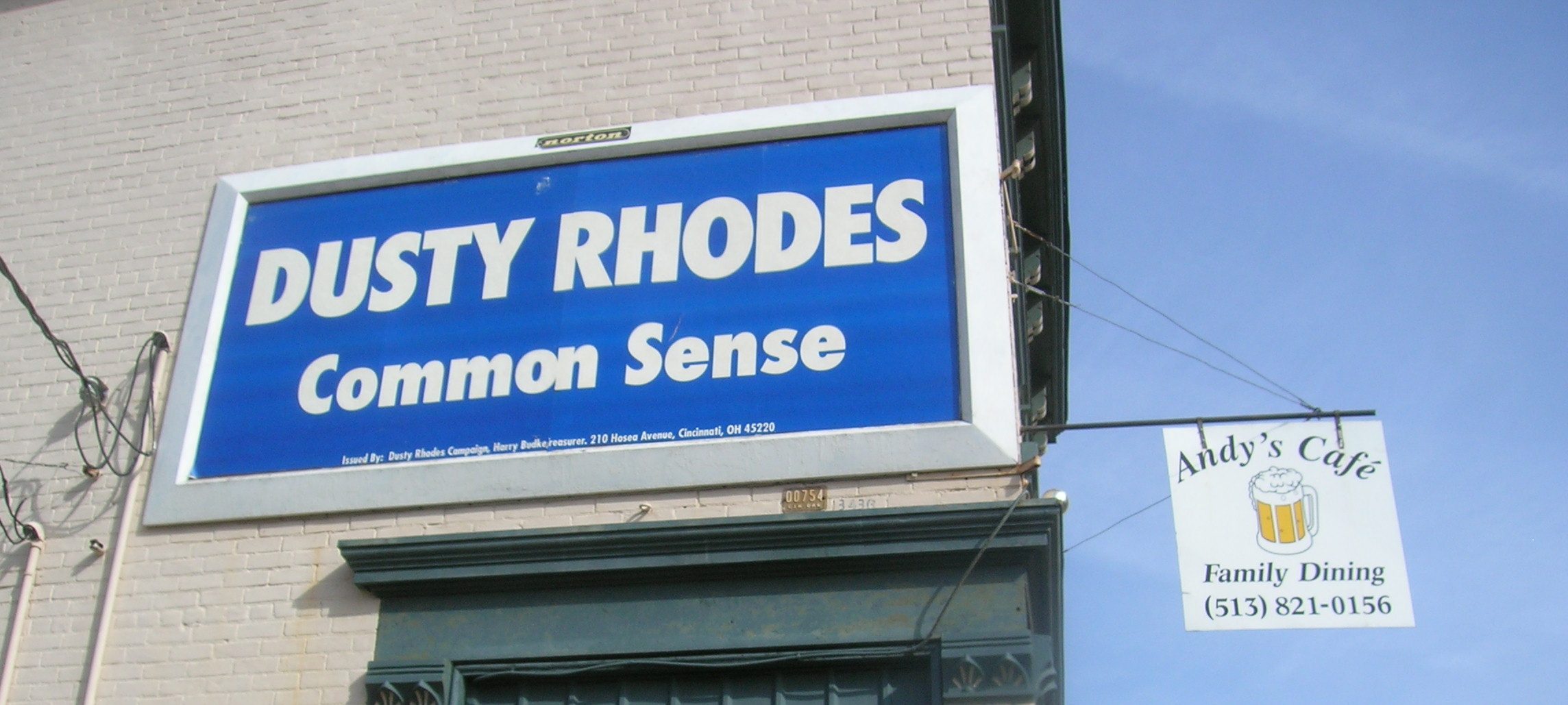

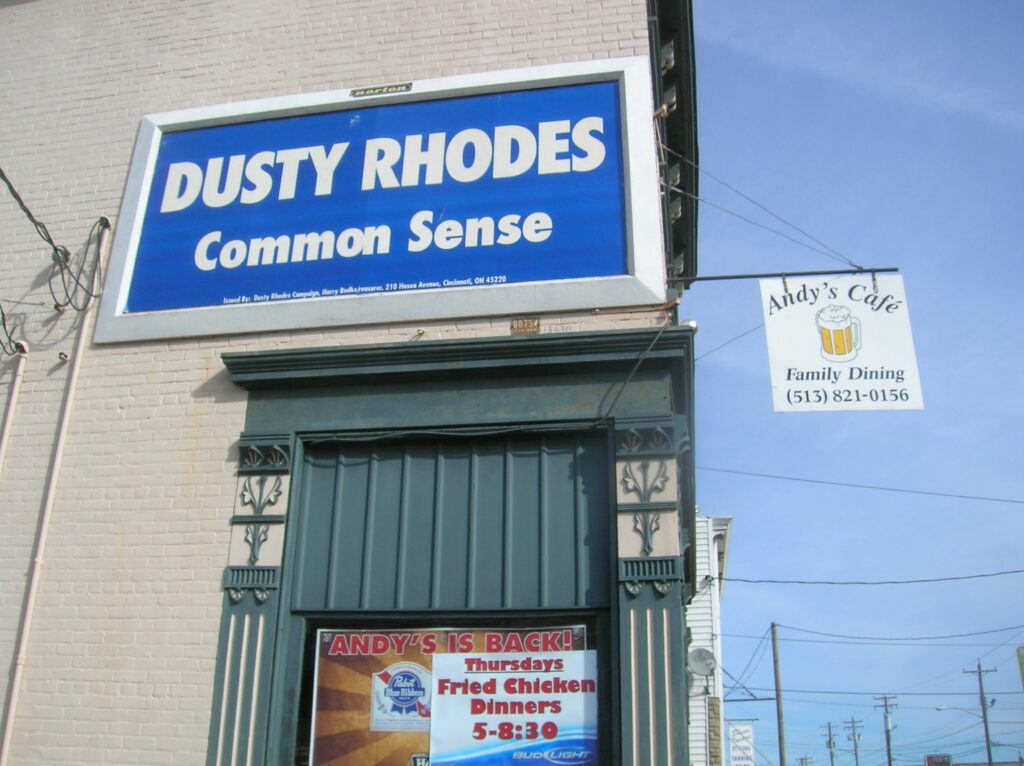

Evidence at the hearing in Cincinnati, the judge said, established that billboards communicate:

- Political speech

- Public service messages helping law enforcement and charities

- Commercial advertising

- Speech created and posted by billboard owners themselves

Can government tax media?

Yes. Media pay plenty of taxes. But selective taxation of press chills First Amendment rights, the judge said.

The power to tax differentially rather than general taxation gives government a powerful weapon against the targeted taxpayer, Judge Hartman wrote, citing the Minneapolis Star case. In that newspaper case, the Supreme Court ruled against a state tax on paper and ink.

Summarizing decades of legal precedent, the judge ruled that government may not single out a narrow group of speakers for unique taxation.

Does government’s need for revenue trump the First Amendment?

Not by itself.

In this case, the judge said, the city had multiple alternatives to balance its budget other than taxing speech on billboards. The city did not demonstrate a compelling interest to justify selective taxation of billboards.

What was the “gag order?”

Cincinnati’s billboard tax included an unusual provision that Lamar and Norton called a “gag order:”

“The tax shall not be stated or charged separately from the rent or other consideration paid by an advertiser… or otherwise reflected upon any bill, statement, or charge made for the sign’s use,” the tax ordinance said. “No advertising host shall state in any manner, whether directly or indirectly, that the tax or any part thereof will be assumed or absorbed by an advertiser, or that it will be added to the rent or other charge.”

The city said its no-stating-the-tax provision would prevent false or misleading claims.

Judge Hartman described the gag clause as “nothing more than an attempt to compel silence and force the billboard owners to suffer the retribution of its customers (or loss of customers) because of increased costs when the real culprit or villain for such increased costs it the government.”

What’s the harm?

The city argued a tax on doing business in Cincinnati does not constitute harm to justify injunctive relief.

Starting on Page 35 of his 39-page decision, Judge Hartman lists harms of targeted taxation of billboards:

- Commercial advertisers could go elsewhere

- Public interest messages would be curtailed

- Some billboards would disappear

- “The result would be fewer voices and messages in the marketplace of ideas,” he said.

Yes, billboards speak.

Download the PDF

Published: October 22, 2018